Parents, community members and Asheville City Board of Education member Joyce Brown had questions about why Asheville City Schools would sign a contract authorizing nearly $90,000 in services from Forthright Advising, a Raleigh-based public relations firm. At a board meeting on Feb. 15, they got little explanation; two weeks later, Superintendent Gene Freeman offered a terse summary.

“Forthright is a company that we’re engaging to help us as we look at our deseg order,” Freeman told the school board during a March 1 work session. “We’re using them to help build the community and get response back from the community.”

First established in 1972 by the U.S. District Court of Western North Carolina, the Asheville school system’s desegregation order was put in place to ensure local leaders were following the Supreme Court’s intent in Brown v. Board of Education. The order was then updated in 1991 to maintain racial balance between schools after resident Bob Brown objected to the divide between mostly Black Randolph Elementary and mostly white Ira B. Jones Elementary.

Now, Freeman suggests, the desegregation mandate may be doing more harm than good. In an emailed response to an Xpress request for comment, he said the system’s changing demographics — only 18% of ACS’ roughly 4,200 students are Black, down from 48% of roughly 3,800 students in 2004 — demand a different approach to racial equity.

“Families of color have unfairly limited elementary school options for their children because the district is mandated to maintain antiquated racial quotas that were put into place 30 years ago,” the superintendent wrote. The order requires that any given school have a minority enrollment “no more than 15% above or below the system minority enrollment and that, whenever possible, minority enrollment be no more than 10% above or below the system minority enrollment.”

Freeman, who is white, did not specify how the system was seeking to alter the order or if leaders were seeking its total elimination. He said only that ACS was “looking into many different approaches to how we support students of color.”

The potential changes come as the system, which has shown North Carolina’s worst gaps in achievement between Black and white students since at least 2015, faces other shifts in how decisions are made. Asheville City Council plans to appoint three school board members on Tuesday, March 23, and on March 9, Council asked the N.C. General Assembly to shift the board to an at least partially elected body.

Whoever takes charge of the district will be tasked with resolving those achievement gaps in a city where equity, community reparations and racial representation have become key goals of governance. What impacts might changing the ACS desegregation order have?

Out of the mix

Academic research on the matter is clear in one respect: Loosening desegregation orders leads to greater racial segregation. In 2011, a team at Stanford University found that this effect was particularly pronounced for elementary schools in Southern school districts with previously low segregation — the type of schools now governed by Asheville’s desegregation order.

Charles Clotfelter, a professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy who leads a joint Duke-UNC Chapel Hill team researching educational diversity, says that’s precisely what happened with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in 2002. After a court decision allowed CMS to replace its Asheville-like plan of magnet schools and racial quotas with a neighborhood-centric approach, a statistical measure of segregation in the district jumped by roughly 80%.

“[CMS administrators] said, ‘If you choose the school in the segment where you live, you’re virtually going to be guaranteed that assignment.’ It turned out that most of the parents of middle-class white kids chose their neighborhood school, and so suddenly things looked a lot more segregated,” Clotfelter explains. “They not only stuck to neighborhood schools, they moved to them.”

Less clear is whether ending desegregation would lead to better academic performance for students of any race. Tiece Ruffin, a professor of Africana studies and education at UNC Asheville, points to a study by the nonprofit Economic Policy Institute indicating that Black children perform better on standardized tests when attending low-poverty, mostly white schools.

“Removal of desegregation plans enforces resegregation, and resegregation stymies equitable access to quality education for Black children,” Ruffin says. Freeman did not respond when asked for evidence that greater school choice would directly reduce Asheville’s racial achievement gap.

Ruffin also notes that the initial wave of school integration in the 1960s and ’70s was generally associated with increased high school graduation rates, better academic outcomes and reduced poverty among people of color. And a 2018 report by the Journey for Justice Alliance, she says, found that schools with high Black and Latino enrollment generally offer fewer opportunities for high-level math, science and arts education.

“When you want to eliminate something, and you haven’t even accomplished the goal of why it was put in place, then why do you want to dismantle it?” Ruffin, who is Black, asks about the push to change the desegregation order while massive racial opportunity gaps remain. “It makes me think that you did not fix the system, you did not remove systemic barriers, you did not do anything to transform around the intent of Brown v. Board of Education, of why we thought we should desegregate.”

Pod people

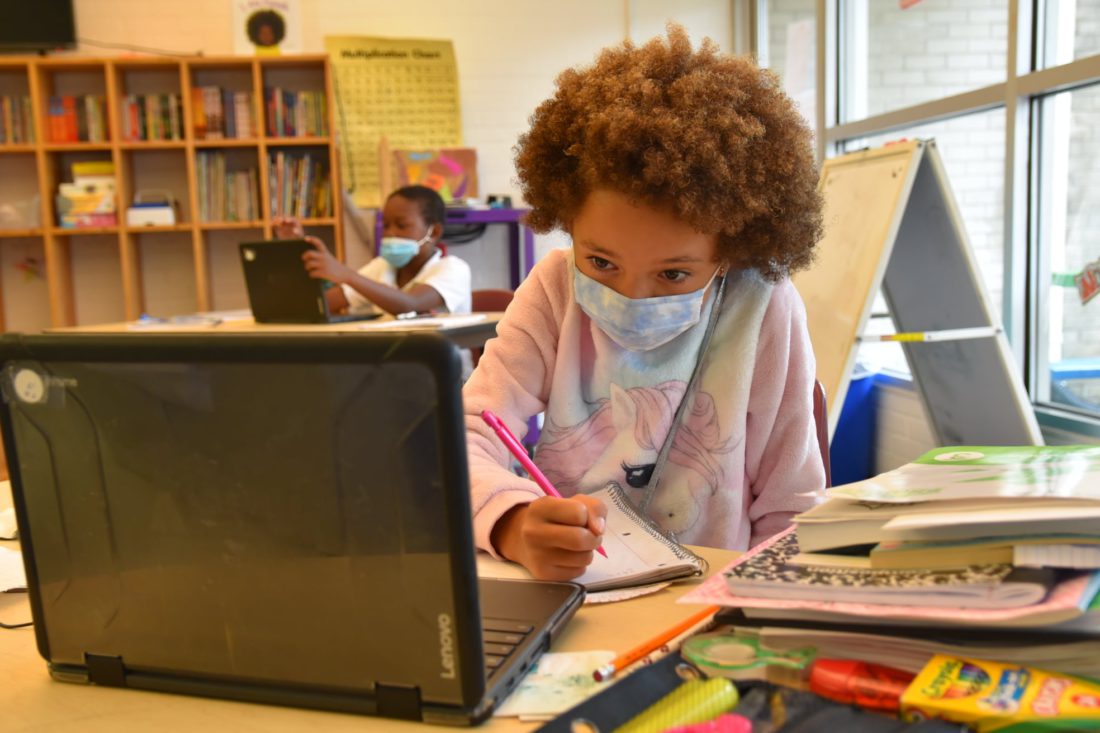

Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has given ACS a chance to experiment with one model for post-desegregation schooling: PODS, or Positive Opportunities Develop Success. These 13 sites, largely located in public housing neighborhoods and community centers, allow students to complete remote learning assignments with access to high-speed internet and support from ACS staff. Because PODS are technically operated by the Asheville Housing Authority and local nonprofits, the program isn’t subject to the desegregation order.

About 75% of the 198 ACS families in PODS as of Feb. 1 were Black, more than three times the proportion of Black families in the overall school system. And according to Micheal Woods, whose nonprofit CHOSEN has been closely involved with the program, all but five families have chosen to remain remote as the district resumes in-person learning. By comparison, 68% of ACS families overall will return to in-person instruction.

“Their kids, who were already falling behind in the traditional classroom setting — they’re seeing a different energy out of their kids, a different desire to learn there,” Woods says about the popularity of PODS among families of color. He also notes that disciplinary issues have plummeted in the remote setting, with a group of students that had received over 400 total infractions last school year receiving only three since the program’s start in August.

As a Black man, Woods says the program has succeeded in part because it brings families, teachers and volunteers of color together in pursuit of a common goal. Students thus feel less pressure to conform to an educational system, he continues, that wasn’t created with their social and emotional needs in mind.

“Schools are spitting out clones of the same thing,” Woods says. “We’re allowing kids to be who they are and not judging them based on what they wear, based on the way that their hair is today. We can help celebrate that.”

Ruffin says some research has shown advantages for students who are matched with teachers of their own race — an arrangement that’s currently difficult to achieve for Black students in the Asheville system, where only 6% of teachers are Black. And she notes that some Black people have preferred to pursue academic excellence through separate schools with Afrocentric education, a strain of thought dating back to 1850s Boston and continuing through Asheville’s own Stephens-Lee High School, which was closed in 1965 after deterioration of the structure from deferred repairs.

But the PODS are primarily staffed by volunteers and ACS teacher assistants, not certified teachers. Away from school buildings, students lack facilities for art, science labs and music. Although learning comparisons are difficult due to the pandemic, more PODS students demonstrated year-over-year declines in English and math proficiency than showed improvement.

And some families may be choosing to remain in the separated settings because they fear the loss of critical extracurricular support for their children. ACS administrators have told parents that they will lose their slots for after-school care if they leave the PODS, a condition not attached to that programming before the pandemic.

The most successful approach to education, Ruffin suggests, would balance the self-determination of different communities with the resources of affluent schools and the proven goods of diversity. “Knowing that the United States is culturally plural, there are benefits of having kids from all different walks of life, race, ability, class, gender, sitting in the same classroom,” she says. “I think that is one peg of the research, that there are benefits of diversity that transcend the K-12 setting as we function as a society.”

Matter of opinion

Thoughts on the desegregation order differ widely among those seeking to set the course of Asheville’s schools. School board Chair Shaunda Sandford supports making changes: “Giving more choice to all families can only be a benefit to future outcomes for our students,” she wrote in an email to Xpress. None of her colleagues, including the three board members up for reappointment — Joyce Brown, James Carter and Patricia Griffin — responded to requests for comment.

Pepi Acebo, who along with Libby Kyles and Jacquelyn Carr McHargue, was endorsed for the school board by the Asheville City Association of Educators, strongly disagrees with Sandford. Instead of pursuing “voluntary resegregation,” he says, ACS should spend more on recruiting teachers of color and expand access to quality preschool programs for students of all races.

Kyles could not be reached for comment, while McHargue says she’d like to see more data on how many families of color have been turned away from their first-choice school before making any changes. That information isn’t publicly available, and when Xpress requested evidence regarding Freeman’s school choice claims, he responded only with “the history of limited choice within ACS for Black and Brown families.”

“From the outside looking in right now, it seems like [changing the desegregation order] is just treating a symptom of what we’re trying to fix, which is our access and gaps in opportunities,” McHargue adds. “For the short period of time that Dr. Freeman has been in leadership, I want to make sure we’re all looking at this from a historical perspective and the current dynamics of our school system.”

Peyton O’Conner, who is on Asheville City Council’s shortlist of school board nominees, agrees with Freeman that the current rules appear antiquated but emphasizes that any shift must be rooted in transparent community dialogue, with a special focus on marginalized residents. Fellow nominee Michele Delange opposes changes to desegregation, saying Asheville’s magnet school lottery is still needed to counter the legacy of discriminatory housing policies like urban renewal. And George Sieburg supports change: “The system in place now privileges white families,” the nominee says, and should be altered as part of a larger effort toward racial equity.

City officials are aware of the school system’s efforts, affirms Gwen Wisler, Council’s liaison to the school board. She and City Manager Debra Campbell attended what ACS spokesperson Dillon Huffman called an “informal brainstorming session” about the desegregation order and other matters earlier in the year.

Although city government collected over $10.15 million in supplemental taxes for the Asheville school system last year and appoints the school board, Wisler declines to weigh in on the desegregation issue. “I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to have an opinion about it,” she says.

New choices

Eliminating racial quotas for existing schools could be just the start of the changes at ACS should the desegregation order loosen. The system could choose to develop a new program from scratch that caters specifically to students of color — an approach already being attempted by several charter schools in the city.

The Francine Delany New School for Children, for example, centers “social justice and preserving the inherent worth and human dignity of every person” in its mission statement and has consistently shown smaller racial achievement gaps than ACS. And the Asheville PEAK Academy, set to open later this year, blasts the city school system’s failures to address racial gaps in its charter application to the N.C. Department of Public Instruction.

“Time and time again, Asheville City School board members, officials and staff have made public statements that blame everything but instruction and disparity in expectations for the low achievement levels of African American students: from poverty to parents to violence in neighborhoods,” the application reads. (Kyles serves as vice chair of the PEAK Academy board.)

According to The Urban News, PEAK will “intensively market the school to Asheville’s African American community.” That approach, argues Acebo, has ACS leaders worried: “If this school succeeds where they are failing, it will further undercut their credibility,” he says.

UNCA’s Ruffin says she is not aware of many Afrocentric public schools in traditional districts; most such institutions are private or organized as charters. While she believes that ACS could succeed in establishing one with sufficient planning and funding, she thinks the district’s resources might be better employed in fixing its existing schools for all children.

“Why don’t you vigorously, intentionally and fiercely revolutionize, reverse, transform the system that currently has kids in it, versus creating a school to be in competition?” she says. “How about you fix what you’re failing at?”

Edited at 4:13 p.m. on March 24 to indicate the correct reason for the Stephens-Lee High School closure.

I wonder if School Board members bothered to look up Forthright Advising. Their Web site offers several links to client projects they have engaged in. What they do is offer spin, spin, spin … but no apparent actual suggestions regarding curriculum or strategies to address the gap. Their whole approach is to make schools look better, not to actually improve them. What a stupid waste of money.

Welcome to Asheville? Kinda the City’s thing, No I know you have been here a while Bothwell but the City School system is a joke. They take all the terrible principals and move them to them central office and this is what you get. The top office is bloated with bad ideas and bad leaders. I am really curious to see what the enrollment numbers look like and how many people left.

Cecil, the Asheville City BoE didn’t technically have to approve it because the cost associated with Forthright Advertising was a few hundred dollars less than what it has to be for them to get approved. Even still, Dr. Freeman was not at the board meeting when this was originally discussed, yet they approved it anyway…without ANY information. The only other person’s name on the document was the district’s attorney who also couldn’t (wouldn’t?) speak to the agreement between ACS and Forthright.

Steve, I wonder what it would take to get the useless folks who work at Central Office out of there before they cause more harm.

Freeman’s argument regarding the percentage of Black students in ACS doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. I ran the numbers based on the US Census. The “problem” isn’t that Black students are leaving ACS. The situation is that there has been a substantial influx of white residents in the past 20 years, reducing the relative number of Blacks in the school system. (The relative percentages are that Black residents as a percentage of the population have dropped from 17 percent to 11 percent, while whites have significantly increased.) So it isn’t some kind of “failure” of ACS to attract students, it is a matter of demographics. It’s sad that the school administration is using false figures to advance a change in policy.